The new State of Global Air South Asia Regional Snapshot on Air Quality finds that exposure to pollutants including fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) continues to be an important environmental health risk. Drawing on a previously published global analysis of air quality trends and health impacts in cities, the snapshot highlights the cities and regions of concerns for both PM2.5 and NO2.

South Asia, already home to enormous populations, is continuing its rapid urbanization; the region includes 3 of the 10 most populous cities in the world (Delhi, Mumbai, and Dhaka) as well as 14 other megacities. Pollution from sources such as energy production and use, industries, transportation, agricultural waste burning etc. impacts the air quality across the region. Across the region, transboundary air pollution is also a significant problem.

The air quality and air pollution conversation across South Asia has increasingly focused on control and mitigation of fine particulate matter or PM2.5. However, as the data show, there is a growing need to consider a comprehensive air pollution management approach at local, national and regional scales, rather than focusing on reduction of particulate matter alone.

Nitrogen dioxide (NO2) deserves more attention across the region.

NO2, a gaseous pollutant belonging to a group of highly reactive gases known as nitrogen oxides (NOx) is a key marker for traffic-related air pollution. Over the last few decades, countries in North America and Western Europe undertook targeted programs to reduce emissions from transportation, energy production and industry resulting in reductions in levels of nitrogen oxides; more recently, China has also begun to reverse the trend, and NOx emissions in the country are slowly and steadily declining. On the other hand, in South Asia, fueled by large-scale programs to expand access to energy to households, expanding industries, and increases in vehicle ownership, NOx emissions have been increasing. For example, in India, major sources of NO2 include coal-based energy production, industrial processes, and on-road transportation.

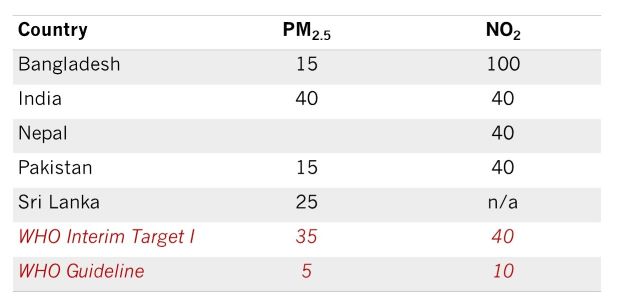

In good news, some countries in South Asia have much more stringent NO2 air quality standards compared to other countries, including the United States, and are in line with interim targets recommended by the World Health Organization (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Annual National Ambient Air Quality Standards for NO2 and PM2.5 (in µg/m3) for countries in South Asia

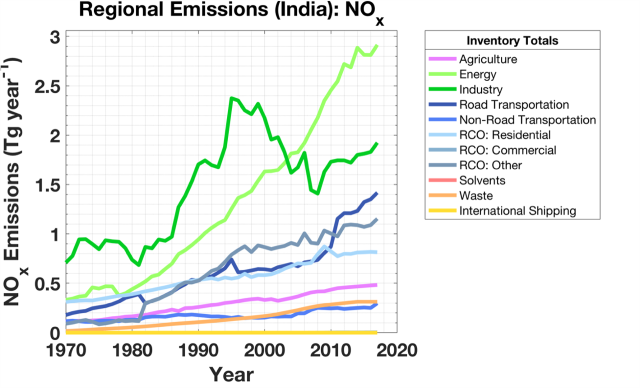

Furthermore, compared to other regions, levels of NO2 in South Asia are relatively low. However, emissions trends indicate that the levels may be increasing over time (Figure 2). For example, in 2019, 68%, 44%, 8%, and 1% of the cities in Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, India and Pakistan met the annual air quality guideline for NO2 (10 µg/m3). Thus, focused sector-specific interventions in the next few years can help ensure that NO2 levels are stabilized and reduced with time in the context of air quality management.

Figure 2: Trend in emissions of nitrogen oxides in India (Source: HEI Research Report 210)

Policy actions such as leapfrogging from Bharat Stage IV (Euro IV equivalent) to Bharat Stage VI (Euro VI equivalent) in India is an example of a policy that will bring important clean air dividends in the next decade; BS VI vehicles provide significant reductions in NOx emissions compared to BS IV vehicles.

Regional cooperation and engagement can yield significant benefits in achieving clean air goals.

The problems, and solutions related to air pollution, are found across South Asia. There is good news — countries in the region have introduced legislation as well as policy programs to address air pollution; most also have air quality standards, largely in line with the interim targets set by the World Health Organization. For example, in India, policies addressing source-specific emissions (for example, transportation) have begun to show dividends. In fact, satellite-based estimates indicate that NO2 levels may be beginning to decline in some Indian cities.

There is growing investment in monitoring air quality and developing air quality management plans. Targeted policies are being implemented across a variety of sectors, from expanding access to clean energy for cooking and heating, promotion of electric mobility, modernizing brick kilns, and developing solutions to reduce burning of agricultural waste. The progress thus far shows that with sustained, evidence-based implementation programs, clean air can be achieved, promoting better health for all. However, considering the magnitude of the problem across the region, collaborative measures on a regional scale are likely to be crucial for more effective solutions.

Note: We would like to thank Anumita RoyChowdhury (Centre for Science and Environment), Dr. Sarath Guttikunda (UrbanEmissions), Asar Social Impact, Dr. Palak Balyan and Bhushan Tuladhar (FHI360) for their feedback and comments.